PET HEALTH

Bladder Stones in Dogs: Everything You Need To Know

Bladder stones (also called calculi, uroliths, or urocystoliths) are mineral compounds that build up and crystallize in your dog’s urine.1 They can vary in size and be quite painful for your pup. When left untreated, bladder stones can create a blockage in your dog’s urethra, and urinary obstructions can develop into a life-threatening situation.1 Fortunately, bladder stones in dogs are highly treatable.

In this article, we’ll discuss the causes of bladder stones in dogs, symptoms to look out for, and treatment options.

What Causes Bladder Stones in Dogs?

Bladder stones usually happen when there are enough urolith-forming minerals in your dog’s system and it’s taking longer than usual for them to pass through. Different types can form under different conditions. Urinary tract infections (UTIs), diet, urine volume and pH, urinary frequency, and genetics can all lead to bladder stones.1

Higher concentrations and retention of salts can also cause urinary stones in dogs. When there is too much salt in your dog’s urine it can lead to a decrease in a dog’s natural ability to block the formation of crystals.2

Types of Bladder Stones in Dogs

There are five different types of stones your dog can develop: struvite, calcium oxalate, urate, cystine, and silica.1

Struvite bladder stones

Struvite bladder stones in dogs form when minerals in your dog’s urine become concentrated and alkaline (i.e., having a higher pH), which causes the minerals to stick together — resulting in crystal formation.3 This often happens as a result of complications from a UTI. UTIs change the acidity of your dog’s urine to a high pH and prevent the minerals from breaking down properly.

Struvite crystals are one of the most common type of bladder stone in dogs, and female dogs are significantly more prone to these types of stones and infections than male dogs.3 Additionally, cocker spaniels, miniature poodles and schnauzers, and bichon frisés may be more likely to develop struvite stones.2

Calcium oxalate bladder stones

Calcium oxalate stones typically form when urine has higher levels of calcium, oxalates, and citrates, and is more acidic (i.e., has a lower pH). The specifics of oxalate stone formation is fairly unknown, but factors that affect it can also include a combination of high dietary carbohydrates and a genetic predisposition.4

Shih tzus, bichon frisés, miniature poodles and schnauzers, Yorkshire terriers, and lhasa apsos are the breeds that may be more predisposed to developing this type of urinary stone.1,4

Urate bladder stones

Urate stones are rarer than other types of bladder stones in dogs and are typically caused by a problem with your pup’s ability to metabolize uric acid or a liver shunt.5 Breeds most commonly affected by urate stones are Dalmatians and English bulldogs.1,5

Cystine bladder stones

Cystine stones result from a genetic problem where your dog is unable to reabsorb cystine from the kidneys as well as they should. However, only certain dog breeds are predisposed to cystine stones — like Newfoundlands, dachshunds, basset hounds, chihuahuas, English bulldogs, Australian cattle dogs, Irish terriers and Yorkies — and even then, nearly all dogs with cystine stones are males.1,6

Silica bladder stones

Little is known about the development of silicate stones. Veterinarians believe they’re related to the ingestion of silica and silicates — potentially from an overly plant-based diet. German shepherds, Labrador retrievers, golden retrievers, and Old English sheepdogs may be more prone to these stones.1,2

Bladder Blockages May Hurt Your Pet and Your Wallet

Symptoms of Bladder Stones in Dogs

There are a variety of signs of bladder stones, including:1,2

- Frequent urination in small amounts

- Difficulty urinating

- Bloody urine

- Abdominal pain

It’s also possible your dog won’t show any clinical signs if the bladder stones are small enough to pass through their system without pet parents noticing them.1 If your dog appears to be experiencing abdominal pain, it’s a good idea to contact your veterinarian so they can help you figure out what’s wrong.

Treatment for Bladder Stones in Dogs

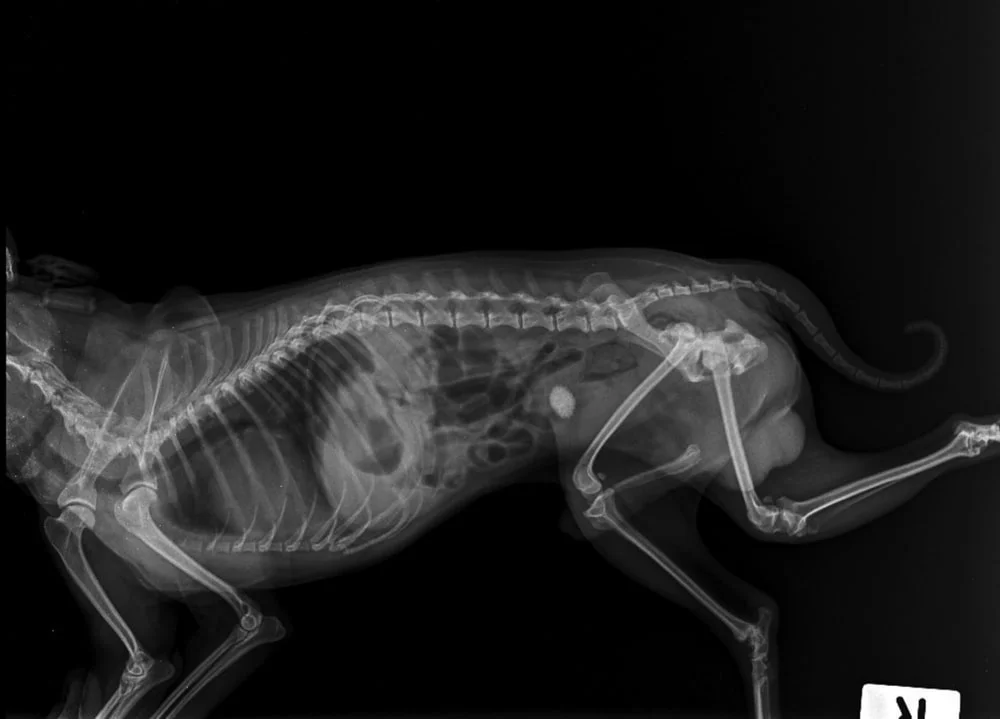

If your veterinarian suspects your dog is suffering from bladder stones, they’ll probably order blood work and a urinalysis, and may need to get cultures of the bladder lining or stone to confirm the diagnosis. They can also take X-rays, which can cost between $150 and $250, or ultrasounds, which can cost between $300 and $600, to spot stones in the bladder or urinary tract. These tests help the vet determine the size of your dog’s bladder stone (or stones) and how to best treat them.1,2

So how do you treat bladder stones in dogs? The exact treatment for bladder stones depends on the type and size of the stone your dog has. Stones may be treated by changing your dog’s diet, administering antibiotics, or performing surgery. In some cases, your dog may be able to pass the stones on their own.1,2 Below is a breakdown of some of the more common treatments.

Therapeutic diet

Struvite bladder stones — and sometimes cystine stones — may be dissolved by feeding your dog a special, therapeutic diet.7 This type of diet can be more costly than the dog food you typically give your furry friend, but a MetLife Pet Insurance plan can help. Take Gunner, for example. He had bladder stones, so his vet put him on a prescription diet, which cost about $120 for each bag. His parents were fully reimbursed because prescription pet foods are covered under our standard plan.8

Work with your vet to find food formulated to control your dog's intake of protein and minerals and maintain healthy urine pH levels.1,2 Once your dog’s bladder stones have dissolved, they may not need to continue eating the special food. However, if your dog suffers from frequent bladder or urinary tract infections, your veterinarian may suggest more permanent dietary changes to help prevent them — like a specific food and limiting treats.7

Antibiotics

Bladder infections are a common cause of struvite bladder stones.2,3 If your dog is suffering from struvite stones, your vet may prescribe antibiotics to treat their bladder infection. If the condition at fault is left untreated, your dog could develop struvite stones again. MetLife Pet can help cover antibiotic costs — just like we did for Coral, a 6-year-old dog with painful bladder stones. The bill for her medication came to $143, but we covered nearly $130.9

Voiding urohydropropulsion

Voiding urohydropropulsion (VU) is a non-surgical procedure for removing small bladder stones with a catheter.1 Your veterinarian inserts a catheter into your dog’s urethra and then flushes the bladder with a fluid solution to expel the stones.10 Usually, this requires sedating your pet.

Surgery

Large stones that can’t be expelled or dissolved — or have created a urinary obstruction — must be removed surgically. Bladder stone surgery (aka a cystotomy) can be stressful for both pets and parents alike, but it’s viewed as a common and quick way to remove stones.1,10 However, it may not be a viable option for all dogs, and it can be expensive.

When Punky had a UTI that resulted in bladder stones, he required surgery to remove them, which cost nearly $4,200. But because his owners had a MetLife Pet policy, they were reimbursed for about $3,800 of the bill.11

Cystoscopy and laser lithotripsy

For small stones, a cystoscopy can be performed where a small camera on the end of a tube is used to non-surgically remove the stone.1,10

In other cases, a cystoscope is used to point a laser at the stone to heat up the molecules. This laser lithotripsy procedure breaks the stone into small particles that can be removed much easier.1,10

How To Prevent Bladder Stones in Dogs

Preventing bladder stones starts with diet and keeping your dog healthy and hydrated. Get your vet’s recommendation for the right food, supplements, and daily water intake based on your dog’s unique needs. Monitor their urine health with a routine pH test and a urinalysis. Keep an eye out for UTI symptoms, and treat the infection to help prevent urinary stones from forming.1,2

Pet Insurance Can Help Cover Bladder Stone Costs

Medical expenses to diagnose, treat, or manage bladder stones can add up and become a financial burden on pet parents whose aim is to keep their dog healthy. However, dog insurance from MetLife Pet can typically help cover some of these costs. With reimbursement rates up to 90%, you can focus more on making sure your dog feels better than the cost of unexpected vet bills.12 Plus, you can get coverage for your pet’s routine vet checkups to help keep them healthy with our Preventive Care plan add-on.

Enroll your pet today, starting with a free quote from award-winning13 MetLife Pet Insurance.